The first 100 days of Jair Bolsonaro

by Fiona Watson, Director of Research and Advocacy

A version of this article was published by The Independent on April 10, 2019

In his first 100 days as President of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro has launched an unprecedented attack on Indigenous peoples, aiming to forcibly assimilate them and plunder their land.

When Jair Bolsonaro became President of Brazil, the country’s Indigenous peoples and their allies around the world braced themselves for the worst. He promised that there would not be one more centimetre of Indigenous land demarcated under his leadership. He announced his intensions to forcibly integrate Indigenous peoples “Just like the army which did a great job of this, incorporating the Indians into the armed forces” but thought it “a shame that the Brazilian cavalry hasn’t been as efficient as the Americans, who exterminated the Indians.”

There are two important lessons we can take from the first 100 days of the Bolsonaro Presidency. The first is that all fears were well-founded, and this racist administration is openly launching an unprecedented attack on Brazil’s Indigneous peoples with the explicitly stated aims of destroying them as peoples, forcibly assimilating them and plundering their land. The second is that there is some hope that this genocidal assault can be stopped. Brazil’s institutions, courts and congress, can provide legal and practical stops if they have the will, and Indigenous people themselves are organising and mobilising against this onslaught on a local and national scale, and have already won notable victories.

Earlier this year, Survival International joined the biggest international protest for Indigenous rights in history as voices and placards were raised all around the globe in solidarity with the Indigenous people of Brazil. The importance, both symbolic and practical, of fighting alongside tribal people cannot be overstated. As well as providing meaningful support to the people involved in the protests, Brazil’s lawmakers, those judges, mayors, congressmen and others not in league with Bolsonaro, are not deaf to voices raised around the world at injustices taking place on their watch.

© Rosa Gauditano/APIB/Survival International

© Rosa Gauditano/APIB/Survival International

On his first day in office, Bolsonaro took the responsibility for the demarcation and regulation of Indigenous territories away from the Indigenous Affairs Department (FUNAI) and handed it over to the Ministry of Agriculture. This policy quite clearly has no other intention than that agribusiness should profit at Indigenous peoples’ expense.

The minister is Tereza Cristina Corrêa da Costa Dias, a former head of the parliamentary agribusiness group, who accepted a campaign donation from a landowner previously charged with ordering the killing of an Indigenous leader. The department official in charge of land issues is Nabhan Garcia, a right-wing former head of the Union of Democratic Ruralists who has fought against the demarcations of Indigenous territory for decades.

But this is not yet set in law. This executive order stands for 120 days and then must pass through congress. As well as the legislature, the judiciary can play a key role in moderating the worst of Bolsonaro’s excesses. The Brazilian Socialist Party (PSB) filed a case with the Supreme Court at the end of January challenging Bolsonaro’s decision to give the Agriculture Ministry authority to determine reservation boundaries. The high court has yet to rule on this particular case, but Brazil’s judges have shown they are willing to stand up to the President.

The government has invoked “national security” to trample over the constitutional rights of Indigenous people. The Waimiri Atroari tribe object to a power line being built on more than 100 kilometers of their land, which, though it will transport electricity to cities like Manaus, will not provide energy to tribal villages or settlements within the reserve. The government has announced that the project will commence on 30th June. Members of the tribe regard this decision as tantamount to a declaration of war, and will likely begin their fightback by taking the government to court.

Bolsonaro is clear that “Brazil does not owe the world anything when it comes to environmental protection” and has changed the procedure for environmental licensing to make it easier to build on Indigenous land. Several new mega-infrastructure projects have been announced, including a dam on the Trombetas River, a bridge over the Amazon River, and an extension of the 300 mile rainforest highway from the Amazon River to the Surinam border.

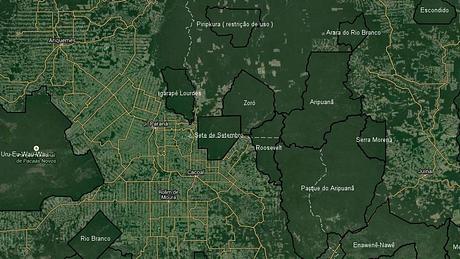

But illegal land invaders don’t wait for legislation to pass or for judges to rule, and at least 14 fully protected Indigenous territories are currently under attack. In what is essentially a frontier war, loggers, miners, oil extractors and cattle ranchers now think the president is on their side. During the Presidential campaign, deforestation surged by fifty per cent and land invasions increased by 150% after he was elected in October last year.

© Google Earth

© Google Earth

Brazil is the deadliest country in the world for environmental defenders, but violence directed at Indigenous people can’t be explained simply as a battle over resources: in many cases, it is quite obviously hate crime. On the night of Bolsonaro’s election victory for example, a health post and a school were firebombed on Pankararu lands in the northeast of the country.

At Survival International, we continue to get dozens of reports from all over Brazil of what sometimes seems like open warfare against Indigenous communities. To stifle NGOs who oppose his interests, Bolsonaro has issued a decree that government authorities can “supervise, coordinate, monitor and accompany the activities and actions of international organizations and non-governmental organizations in the national territory.”

There have been threats to expel environmental groups and Ricardo Salles, the new environment minister, has suspended all government partnerships with NGOs in the country for three months. He believes that protected Amazon areas hold up development and has advocated for commercial farming and mining on Indigenous reserves.

The administration even launched an attack on Indigenous health. The regime proposed to end the Indigenous healthcare system (SESAI), a decentralized care model with 34 Special Indigenous Health Districts, run in collaboration with local communities and catered to their unique needs. Instead, Indigenous patients would just access the same (already inadequate and over-stretched) municipal services as everyone else in the district. Health Minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta said “For 600,000 Indigenous people, the resources the country puts in – I think few countries in the world put in that much.”

The proposal sparked outrage and protest among Indigenous peoples all over the country. Fearful for their lives, and the lives of their children and elderly, they worried about the lack of provision for Indigenous languages and were concerned their needs could not be met by a system designed by and for people living very different lifestyles to them and with staff who knew nothing of their lives and circumstances. From Paraná to Rondônia, from Pernambuco to Mato Grosso do Sul, Indigenous groups occupied public buildings and highways in support of SESAI. The Minister backed down, and made public assurances that the Indigenous healthcare system will not be abolished only a week or so after the proposition was first floated.

This victory is encouraging and important, but all this is far from over: after all, this is only the first 100 days. Sydney Possuelo, a former Head of Department at FUNAI and a great champion of the rights of Brazil’s Indigenous peoples, said: “The situation of Brazil’s Indigenous people has never been very good. But in 42 years working in the Amazon, this is the most dangerous moment I’ve seen.” He is quite right, and the President’s open worship of dictatorship, brutal repression, state-sanctioned violence and extra-judicial murder, raises the terrifying prospect that what we have seen so far in his first 100 days may be, in more ways than one, only the beginning.

__________

More than 150 million men, women and children in over 60 countries live in tribal societies. Find out more about them, the struggles they face, and how you can help – sign up to our mailing list for occasional updates.